|

Vol.

59 (3) 2004 |

INVESTIGATION OF THE FIRST TRANSMISSIBLE GASTRO-ENTERITIS (TGE)

EPIDEMIC IN PIGS IN ISRAEL

Brenner, J.1, Yadin,

H.1, Lavi, J.4, Perl, S.2, Edery,

N.2, Elad, D.3, Bargut, A.4, Pozzi,

S.4, Lavazza A.5, and Cordioli P.

5

1. Division of Virology and Preventive

Neonatal Diseases Unit,

2. Pathology and 3. Bacteriology, Kimron

Veterinary Institute, 50250, Bet Dagan,

4 . Freelancer Veterinary

Surgeon, Israel and 5. Istituto Zooprofilatico Sperimentale della

Lombardia e dell’Emilia-Romagna “Bruno Ubertini” Via Bianchi 9, Brescia

(BS), Italia. |

|

Abstract

Transmissible gastro-enteritis (TGE) is a

contagious disease of pigs that occurs as explosive epizootics. This

communication reports on the evidence that we gathered in order to confirm

the first epidemic of TGE in Israel and external validation corroborated

our clinical suspicion and laboratory findings.

Our Discussion forum is open for

your comments on this article Our Discussion forum is open for

your comments on this article

|

Materials

and methods Results

Discussion

back to top

Introduction

Transmissible

gastro-enteritis (TGE) is contagious disease of pigs that occurs as explosive

epizootics. TGE is caused by the TGE virus (TGEV), a member of the

coronaviridae. A distinct respiratory variant the Porcine Respiratory Corona

Virus ( PRCV) has been recognized since the 1980’s, a deletion mutant of the

TGEV (1). Two other coronaviruses antigenically distinct are the Porcine

Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV) and the Hemagglutinating Encephalitis Virus (HEV)

(2).

TGEV is a common cause of

diarrhea in pigs, affecting all ages but significant deaths only occur in

suckling pigs, with the severity related to the age of the animals infected.

Almost all susceptible piglets under 10 days of age die within few days of

exposure, but the mortality decreases the older they become. Only mild signs

such as vomiting, regurgitation and agalactia are present in the lactating dams.

In an endemic situation, namely, in vaccinated animals and/or where the acute

wave has faded, sporadic diarrhea in older animals and post-weaning animals in

contaminated nurseries are the spare clinical evidences of TGEV infection. As a

member of the coronavirus group, TGEV is primarily an enteric virus, destroying

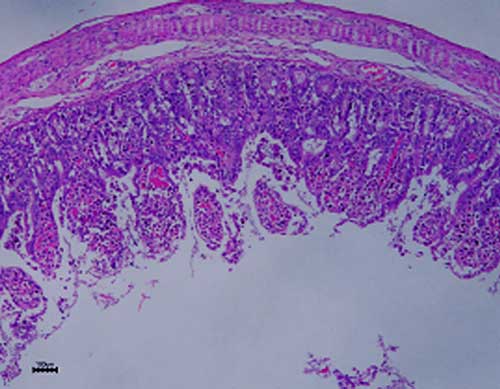

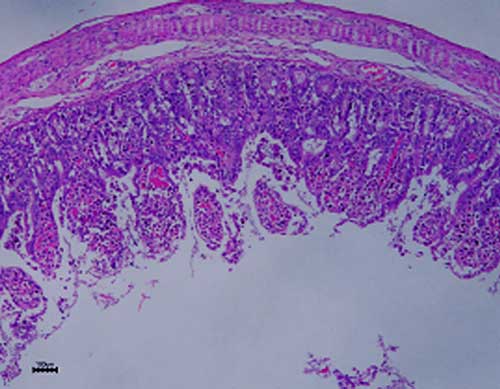

enterocytes of the small intestine (Fig. 1), causing villous atrophy.

Extra-intestinal sites of virus multiplication include the respiratory tract and

mammary tissues (3,4,5), but the virus is most readily isolated from the

intestinal tract and feces.

The first report of clinical

disease in pigs caused by coronaviruses dates to 1946 (6) and TGE occurs

throughout the world. The emergence of PRCV coincided with the disappearance of

TGEV in Europe (7). In mid 1980’s, a previously unrecognized porcine coronavirus

spreading through Europe was identified (8). The name porcine epidemic diarrhea

virus (PEDV) was adopted (9). At present, PEDV has been identified in most

swine-producing countries, except in the Americas (9).

When the TGEV spreads within

a fully susceptible herd with no previous history of TGEV infection, up to 100%

mortality is expected among newborn pigs, showing marked diarrhea and

dehydration in weaned pigs, while inappetence, vomiting and

diarrhea are typical signs in adult animals. Partial or total agalactia of sows

is common (5,9).

The Israeli pig industry benefits from a particular

epidemiological situation. Due to religious customs in the middle east, where

the Jewish and Muslim religions prevails, the pig industry is largely isolated,

and far away from any zone with intensive pig industry. Consequently, very few

epidemics have been recorded among the Israeli pig herds. This communication

reports on the first epidemic of TGE in Israel. The investigation was carried

out pursuing diagnostic methodology of emerging diseases.

Introduction

Results

Discussion

back to top

Materials and Methods

Case

description

The first cases of diarrhea followed by dehydration and

death of newborn piglets, 1 to 7 days old were noted in one pigsty in northern

Israel on May 7th 2004 and the episode gained epidemic proportions, with

mortality as high as 70 to 80% during the first week of life and proportionally

less in convalescent groups of piglets. The area where this outbreak occurred is

nicknamed the “swine hill” which is located near Evlin. This hill is about 1.5

by 1.5 kilometers. Thirteen pig herds are concentrated in this restricted zone.

One to two days later after the first outbreak, other herds reported the same

clinical signs. Additional clinical signs that accompanied this outbreak were

vomiting and regurgitation and a partial agalactia in lactating sows. Two

piglets of 2 days old were brought to the Kimron Veterinary Institute (KVI) for

post mortem examination. The histological examination of the small intestine

revealed typical (4,9) villous atrophy, suggesting an enteric virus infection.

On May 24th a group of investigators from the Kimron

Veterinary Institute paid a visit to one of the affected farms. Upon the visit,

the clinical manifestations appeared as reported by the local practitioner. The

followed materials were collected on the farm: 5 individual diarrheic feces

samples, 5 moribund piglets, 6 blood samples with an anti-coagulant (3 of

diseased and 3 of convalescent animals, respectively) and 10 blood samples

without anti-coagulant (5 from diseased animals and 5 from convalescent ones,

respectively). Four of the 5 moribund animals arrived alive and one died during

transport. They were sacrificed immediately upon arrival and the feces and

intestinal segments as well as biopsies of all the internal parenchyma and

brain, were prepared for histopathological examination. An additional two sets

of the same tissues were store at -20oC, for further analysis. One

set of intestinal segments from the 5 piglets were shipped to the Istituto

Zooprofilatico, (IZS) Brescia, Italy.

One week later

another batch of diarrheic feces arrived to KVI from newly infected herds. This

batch comprised nine pooled feces; each sample represented one infected

litter.

Antigenic identification

Assuming that if

porcine and bovine coronaviruses share common antigenic epitopes, we used the

bovine assays for the diagnosis of rotavirus and coronavirus (Bio-X Combined

Digestive ELISA Kit, for antigenic diagnosis in bovine faeces of rotavirus,

coronavirus, E coli K99, B-6900 Marche-en-Famenne, Belgium) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions.

Another set of antigen diagnosis was carried

out at the IZS, using the immuno-fluorescence (IFA) on intestinal sections,

electron-microscopy (EM) and immuno-EM (IEM) with specific anti-TGEV and

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Kim et al., 12), and virus isolation.

For the IFA and for the IEM assays performed on the

intestinal sections, hyperimmune serum specific for porcine coronavirus was

used.

Serology

This assay was performed at the IZS in Brescia,

using a commercial kit ELISA (INGENASA) for the presence of anti-TGEV antibodies

in infected and convalescent animals.

Necropsy

All the parenchyma samples were processed

regularly and were prepared for staining with H&E on samples embedded in

paraffin.

Hematology

Biochemical and hematological profile was

done on all the blood samples.

Bacteriology

The routine laboratory diagnostic

procedures were used as described elsewhere (10).

Introduction

Materials

and methods Discussion

back to top

Results

Antigenic discovery

|

In total 63% of the fecal samples were positive

for bovine corona virus antigen(s) (6/10 and 6/9 for the first and second

sets of samples, respectively).

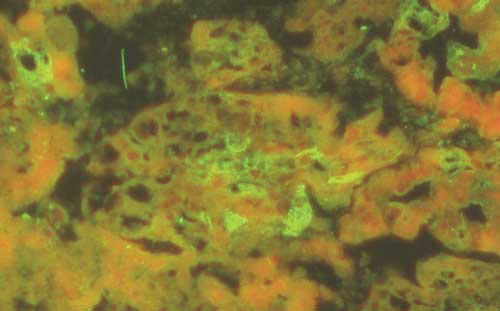

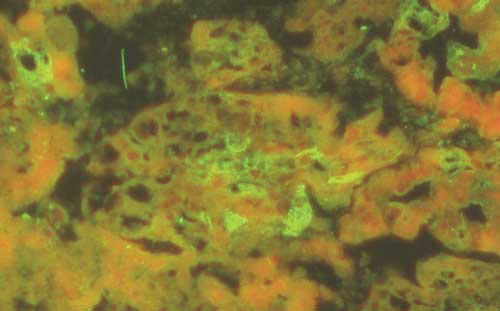

All the assays combined together, namely, EM and

IEM, PCR and IFA (Fig. 2) performed at the IZS in Brescia, showed that in

all the 5 samples TGEV was present although none of the assays alone could

identify the TGEV in all the samples (Table 1). Virus

isolation succeeded in two out of three diseased piglets. This isolation

attempt was performed on piglets originating from a farm on day 45 of the

ongoing TGE epidemic (Lavazza and Cordioli, personal

communication).

Serology

The sera derived from

diseased animals had a very weak ELISA anti-TGEV reaction while the

convalescent sera showed a very strong anti-TGEV reaction.

Necropsy

Villous atrophy

was noted, suggesting an acute enterovirus infection (Fig. 1). Massive

infiltration of inflammatory cellular components, vacuolization of

enterocytes and destructive process were all sequelae of the ongoing

infection. |

Figure 1. Villous atrophy and vacuolization of enterocytes

with a massive infiltration of inflammatory cellular

components. |

|

Hematology

The WBC, lymphocyte and

neutrophil counts are presented in Table 1.

As seen in Table 2, the hematological profile of

the diseased animals shows a remarkable lymphopenia and a moderate

neutrophilia. The L/N ratio range is a characteristic haematologic picture

of acute viral attack.

Bacteriology

All the

bacteriological assays resulted negative for the presence of

enteropathogenic bacteria including Clostridium perfringens type C, the

causative agent of porcine enterotoxemia in piglets. |

Figure 2. Immunofluorescence

staining of the small intestine with monoclonal anti-porcine corona virus

antibody.

|

Table

1 -

A Summary of the PCR, ME, IEM and IFA results from the IZS

laboratories .

|

Animal

Number |

TGEV-PCR |

ME |

IEM |

IFA

pools |

|

1 |

+ |

- |

- |

|

|

2 |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

|

3 |

- |

+/- |

+ |

+ |

|

4 |

- |

+ |

+ |

|

|

5 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Table

2.

Range of White blood cells, lymphocyte and neutrophil counts and ratio N/L of

diseased and convalescent animals

|

|

WBC |

Lymphocytes |

Neutrophiles |

L/N* ratio

range |

|

Diseased

|

9-14.2x103

|

3.1-4.5x103 |

3.8-7.6x103 |

0.3-0.5/1

|

|

Convalescent |

11-17.8x103 |

9.7-11.5x103 |

0.8-4.6x103 |

3 to

10/1 |

*lymphocyte/neutrophil

ratio.

Introduction Materials

and methods Results

back to top

Discussion

The Israeli intensive pig industry is

isolated from other areas of farming. Moreover, it was maintained in

quasi-closed premises, 13 pig herds in one region, with no other industrial

pigsties within approximately 100 km. Due to this particular situation, Israeli

Veterinary Services and KVI lacked species-specific diagnostic tools for the

diagnosis of specific swine diseases. Nevertheless, we have diagnosed TGEV

antigens in relatively short time by using non-species specific diagnostic kit.

A specialized laboratory (IZS) that deals regularly with swine diseases has

found the TGEV in the same samples, reconfirming our primary results.

The differential diagnosis (11) of enteric

neonatal diseases deals with many possible causative agents.

The typical findings of villous atrophy

(Figure 1) and lymphopenia (Table 2), pointed toward a probable viral (acute)

attack. The clinical manifestations especially the age distribution of the

diseased animals at risk, the rapid spread of the disease among the pigsties,

its high mortality rate, the antigenic ELISA positive reaction in 63% of the

fecal samples submitted to KVI and the confirmations tests from the IZS, lead us

to the conclusion that TGEV is responsible for this episode.

Whether the virus originated from bringing

or smuggling of infectious material from abroad, or from the wild boar

population is a matter of speculation.

Introduction Materials

and methods Results

Discussion

back to top

LINKS TO OTHER ARTICLES IN

THIS ISSUE

References

1. Pensaert, M.B. and DeBouck, P.

and Reynolds, D. J. An immunoelectron microscopic and immunofluorescent study on

the antigenic relationship between the coronavirus-like agent CV777 and several

coronaviruses. Arch. Virol. 68: 45-52 1981.

2. Transmissible gastroenteritis.

In: O. I. E. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals

Fifth Edition, 2004, pp 792-801.

3. Kemeny, L. J., Wiltsey, V. L. and Riley,

J. L. Upper respiratory infection of lactating sows with transmissible

gastroenteritis virus following contact exposure to infected piglets. Cornell

Vet. 65: 352-362 1975.

4. Cooper V.L. Diagnosis of neonatal pig diarrhea.

Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Prac 2000.

5. Prithchard, G.C. Transmissible

gastroenteritis and porcine epidemic diarrhea in Britain. Vet. Rec. 144:

616-6181999.

6. Doyle, L. P. and Hutching, L. M. A transmissible

gastroenteritis in pigs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 108: 257-259 1946.

7. Wood,

E. N. An apparently new syndrome of porcine epidemic diarrhea. Vet. Rec. 100:

243-244 1977.

8. Pensaert, M.B. and DeBouck, P. A new coronavirus-like

particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch. Virol. 58: 243-247

1978..

9. Saif L. J. and Wesley, R.D. Transmissible gastroenteritis and

porcine respiratory coronavirus. In: Diseases of Swine, 8th Edition, Iowa State

University Press/ Ames, Iowa USA, pp. 295-325 (Eds: Straw, B. E, D’allairte, S.,

Mengeling. W. L., Taylor, D.J.) 1999.

10. Brenner, J., Elad, D., Van Hamm,

M., Marcovic, A. and Perl, S. Microbiological and pathological findings in

faeces and carcasses of young calves suffering from neonatal diseases. Isr. J.

Vet. Med. 50: 21-24 1995.

11. Liebler-Tenorio, E. M. Pohlenz, J. F. and Whipp

S. C. Diseases of the digestive system. In: Diseases of Swine, 8th Edition, Iowa

State University Press/ Ames, Iowa USA, pp. 821-831 (Eds: Straw, B. E,

D’allairte, S., Mengeling. W. L., Taylor, D.J.) 1999.

12. Kim, L., Chang,

K-OK, Sestak, K., Parwani, A. and Saif, L.J. Development of a reverse

transcription-nested polymerase chain reaction assay for differential diagnosis

of transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine respiratory coronavirus from

feces and nasal swabs of infected pigs. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 12: 385-388.

2000.

1.

![]() Our Discussion forum is open for

your comments on this article

Our Discussion forum is open for

your comments on this article